Silent killer claiming thousands

The scourge of liver fluke infection can be halted if there is a will to take action

Each year, 14,000 Thais die from cancer that manifests in their bile ducts caused by a silent killer known as liver fluke disease.

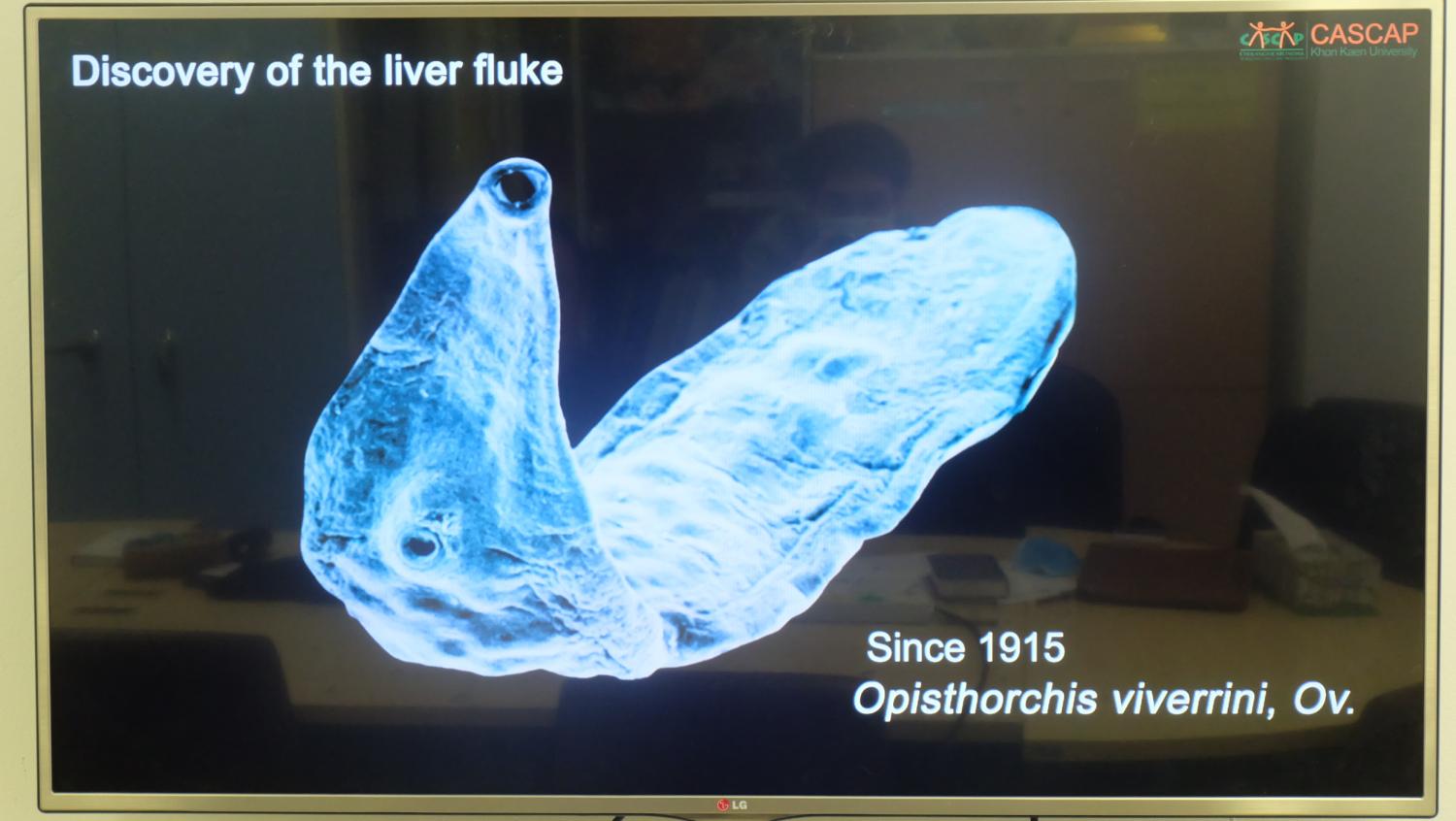

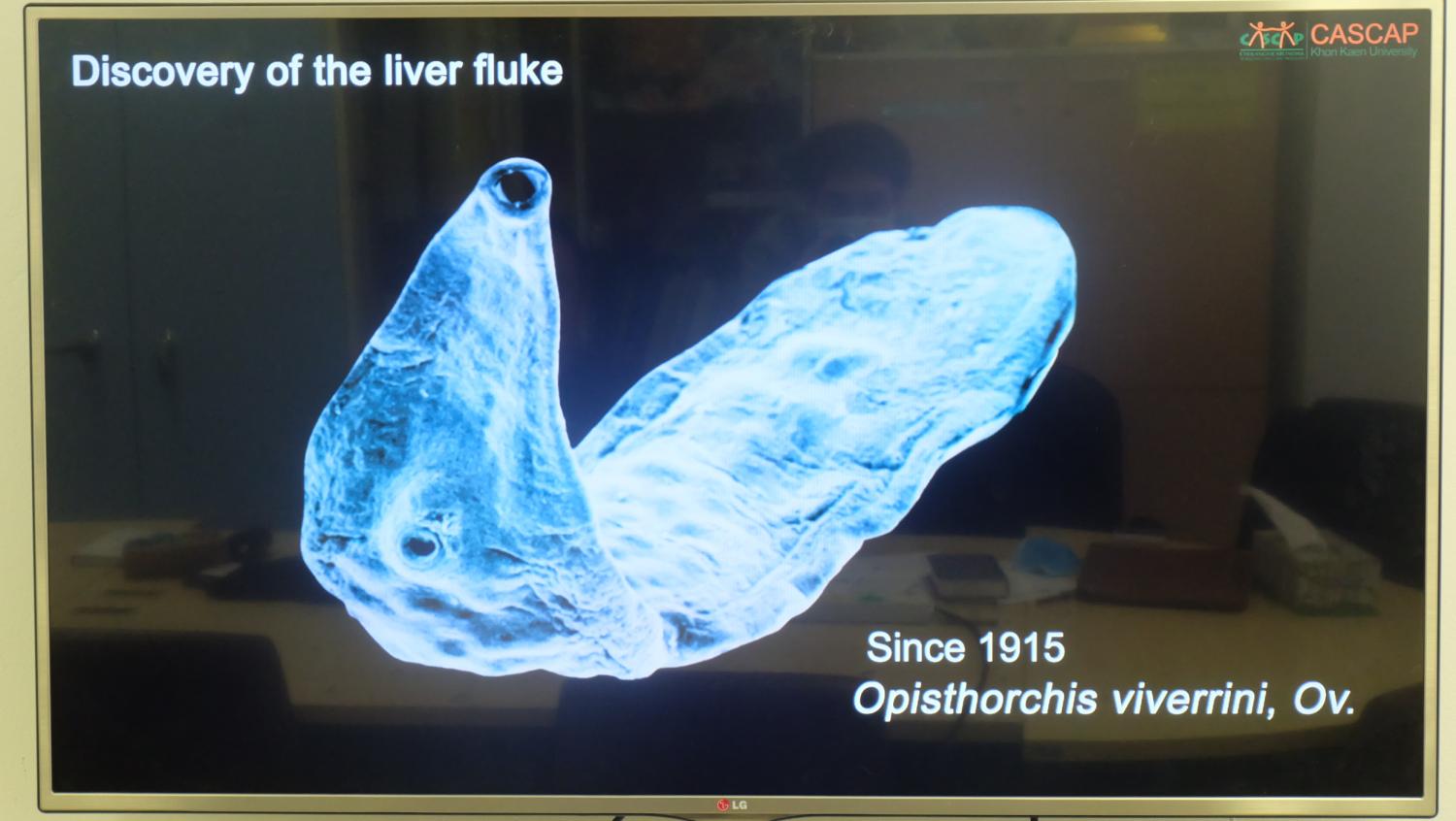

Despite sounding innocuous, liver fluke disease — which is caused by a parasite — is insidious in its nature. The parasite can live inside the liver for 20 years, feed on digestive fluid bile and infect and turn the bile duct into carcinogenic tissue. Each year, six million people in Thailand are infected, most of them villagers of the Northeastern region.

In Khon Kaen, the largest Northeastern province, there is a special ward to handle cases of cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer).

The ward is the Cholangiocarcinoma Centre of Excellence at Srinagarind Hospital on the campus of Khon Kaen University. It is known as the world’s largest cholangiocarcinoma ward.

The ward is so famous even patients from Laos cross the border to get treatment there. Liver fluke infection often occurs to those who eat raw fish and meat over a long period of time.

Phongpayom Janpengpen said his father, a cancer patient who came to receive treatment at the ward, is a victim of the local food culture.

Mr Phongpayom’s father is an example of middle-aged Northeastern men who develop bile duct cancer from eating raw fish meals, especially Koi Pla, a dish made from raw fish.

“In past days, villagers caught fish in the river and cooked them in their own local way, eating them almost raw,” he said.

After removing their heads and scales, villagers chop fish into pieces and make Koi Pla.

“They ate it with alcohol in the mistaken belief that it could kill germs,” Mr Phongpayom told the Bangkok Post as he waited for his father’s treatment.

“The consumption of raw fish has faded over time due to health literacy, but this local food culture still persists nevertheless.”

The European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma reported that the Northeast region of Thailand has the world’s highest incidence of bile duct cancer, with the ratio of 85:100,000.

It is the leading cause of death in Isan men and women.

Cholangiocarcinoma Research Institute (Cari) director Narong Khuntikeo said carcinogenic liver flukes are found in carp fish, a common dish in Southeast Asian countries, especially Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Southwest China.

“Most patients came to hospital when it was too late with jaundiced eyes and abnormal abdomens which were built up by fluid,” he said during a media press trip organised by Cari from June 26 to 28.

The disease is “slow burn” — it can take 30 years to manifest itself.

World capital of malaise

Assoc Prof Narong said Khon Kaen has been called “the world’s capital city of bile duct cancer because the ratio of patients stands at 1,000:100,000, against the “acceptable” threshold of 10:100,000.

Geography plays a big role in the cause of liver fluke.

Khon Kaen has two major rivers — the Phong and the Chi Rivers bring in plenty of fish and trade yet also harbour disease.

Liver flukes often break out in waterways that run through provinces that the Songkhram River runs through, including Sakon Nakhon, Udon Thani, Nong Khai, Bueng Kan and Nakhon Phanom provinces.

Parasites thrive in these waters and are carried through by these rivers.

Dr Narong, a veteran surgeon, said parasites in the liver can produce 500 eggs every day.

When they come out of human bodies in faeces, unsanitary waste management can leak the parasitic eggs into canals.

“These eggs hatch out and grow into cercariae [tadpole-shaped larvae]. Then they swim in search of new hosts and attach themselves to carp fish. When people, dogs, and cats eat them raw, they will be infected,” he said.

The life cycle of liver flukes starts as soon as children aged as young as 10 eat cyprinid fish infected with metacercariae (encysted larvae). Once inside human bodies, they emerge from cysts and mature.

Infected children normally die of bile duct cancer when they reach middle age, he said.

High-risk traditional dishes include Koi Pla, Pla Som [sour fish], and Pla Ra [highly salted fish], all of which can infect consumers if they do not meet safety standards. They must be cooked or fermented for a long duration. While Pla Som must be kept for over three days, Pla Ra must be preserved for over one month.

Fluke-free Thailand

Having been a surgeon for more than 30 years, Dr Narong, now retired, said he decided to launch the Cholangiocarcinoma Screening and Care Program (Cascap) in 2014. Funded by Khon Kaen University, he pushed forward the project until it sailed through the National Health Assembly in 2014 and cabinet in 2015.

“However, the Ministry of Public Health did not press ahead with its 10-year strategic plan for the elimination of liver fluke parasites and bile duct cancer [2016-2026],” he said. “Accordingly, I sought financial support from the National Research Council of Thailand to carry out the Fluke Free Thailand project [in 2016].”

Dr Narong said his team has developed a regional cohort network system to trace patients in 29 provinces and link them with over 4,000 hospitals nationwide. With the help of local public health workers, over two million infections have been registered.

“These patients can now register online for liver fluke infection and bile duct cancer screening at hospitals,” he said. “At the same time, we train doctors to operate on bile duct cancer. We are trying to ensure patients receive adequate and timely treatment.”

Dr Narong said the project has provided financial support of up to 50,000 baht each to those who cannot afford surgery, drugs, and chemotherapy. Those who have early-stage bile duct cancer removed can live for another five years, representing 47%.

He said the scheme has launched educational campaigns in schools and faecal sludge management in municipalities to ensure parasitic eggs will not leak into canals. If faeces are left in the sun for 28 days, parasitic eggs will die.

Local administrations and municipalities are taught to use a waste management system to collect daily excrement in communities instead letting the parasite-filled waste be discharged into rivers. The facility, such as the one in Khon Kaen, comprises 30 large slot bins. The system can take up waste from five trucks. Dried waste has been used as organic fertiliser as a result.

Dr Narong has been waging the Fluke Free Thailand campaign from one district to another in the hope of garnering wider support from the government who can place the issue at the top of national health agenda.

He recalled one of his bile duct cancer patients. An ill father desperately wanted to live for another year just to drive his daughter in her first year to university, but the surgery turned out very well, giving him a longer lease of life.

“He lived for another four years and eight months. In that time, his daughter graduated with a bachelor’s degree in education and became a teacher,” he said. However, he said, the man and other patients should not have died. “Nobody will have to count down their remaining days if we take action to end the vicious circle of liver fluke in the first place,” he said.